Word embedding models: A very short introduction

Word embedding models may be old news for computer scientists in the field of machine learning, but the excitement they are generating among digital humanities scholar is still quite effervescent. Formally published research by literary scholars on the topic is, however, still comparatively thin on the ground, though I’ve tried to do my bit towards rectifying that in an article in a Modernism/Modernity Print Plus cluster which explores various ways that word embeddings can be used with periodicals. In the meantime, though, I find myself increasingly in need of a brief and non-mystificatory introduction to the concept to which I can direct literary researchers and other humanities folks, so I’m parking one here.

To understand a word embedding model, you can begin by thinking of it as a mathematical construct which translates the relationship between every word in a corpus and every single other word in that corpus into a set of numbers (for the linguists, we are talking types rather than tokens). You can then do calculations with these numbers which tell you, to a high degree of precision, about the relationships between these words. The mathematical construct is conceptualized in multidimensional space, and the relations between words exist as vectors, producing what is known as a vector space model. Such models represent each word as, in Katrin Erk’s phrase, “a point in high-dimensional space, where each dimension stands for a context item, and a word’s coordinates represent its context counts”. This high-dimensional space is normally reduced down from some tens of thousands of dimensions to a few hundreds, so that calculating the proximity of words won’t slow your laptop down to a crawl.

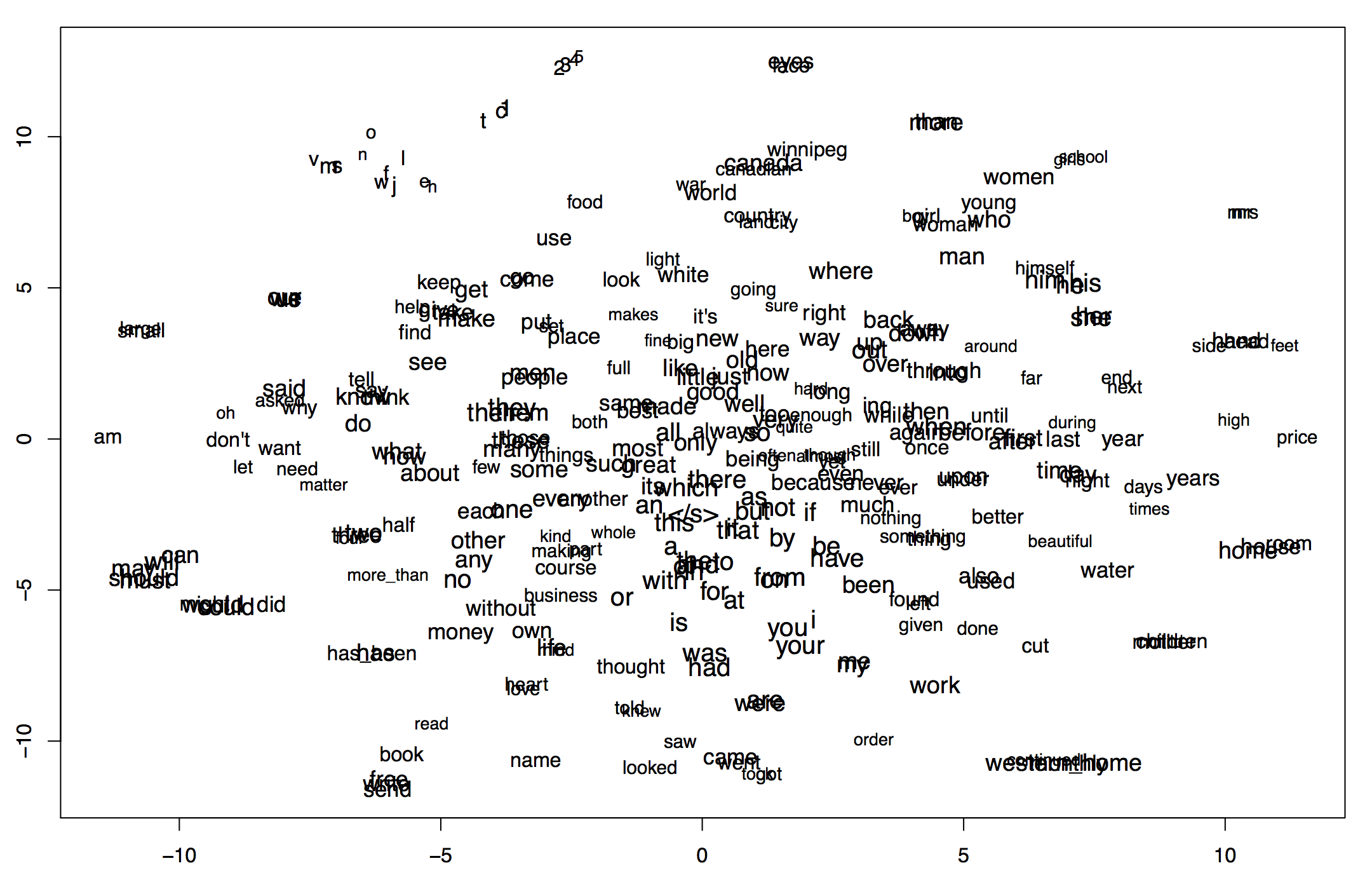

If you want to represent these relationships between words on the page or the screen, the model’s dimensionality needs to be reduced still further to two or three dimensions using techniques for dimensionality reduction such as t-SNE (t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding), as shown below.

Plot showing a vector space model trained on the digitized text of the twentieth-century Canadian periodical The Western Home Monthly reduced down to two dimensions using tSNE.

The basic premise of such a visualization is this: if words appear in spatial proximity to other words in these reduced-dimensionality representations, this means that they occur in the corpus in similar contexts, ie. near the same sorts of words. In the plot above, you will notice a collection of common verbs clustering together at the bottom of the plot in the middle (was had thought were are told knew saw came looked went), some gendered terms towards the top right (girl boy man woman women girls himself him he), and at the top left, a collection of numbers and letters that suggest OCR errors or artefacts of digitization (so in this case it is identifying not a semantic resemblance, but another kind of resemblance – an error). The important thing to understand is that there is no semantic work going on behind the scenes, nothing telling the model that woman and women are the singular and plural forms of the same noun: the model puts these words into a spatial arrangement based only on how often and to what extent they appear near similar words.

To understand why spatial proximity in a vector space model is relevant, it’s helpful to understand a concept which is likely to appear curiously reductive to those trained in textual analysis: that words which are close together will tend to be similar in their meanings. Within linguistics this is known as the distributional hypothesis, and can also be expressed as “words which are similar in meaning occur in similar contexts” (Rubenstein and Goodenough 1965). In pursuit of these similar meanings—and what they may tell us about individual words—word embedding models capture the full set of an individual word’s contexts, ie. all the co-occurrences of that word with all the other words in the corpus. In mathematical language, this is termed the distribution of that word’s contexts. This distribution is represented as a vector, a mathematical entity which can be understood as a (usually very long) list of numbers, which are the set of co-ordinates specifying where the vector (ie. the individual word understood in terms of all the words that co-occur in proximity to it) is located in multidimensional space.

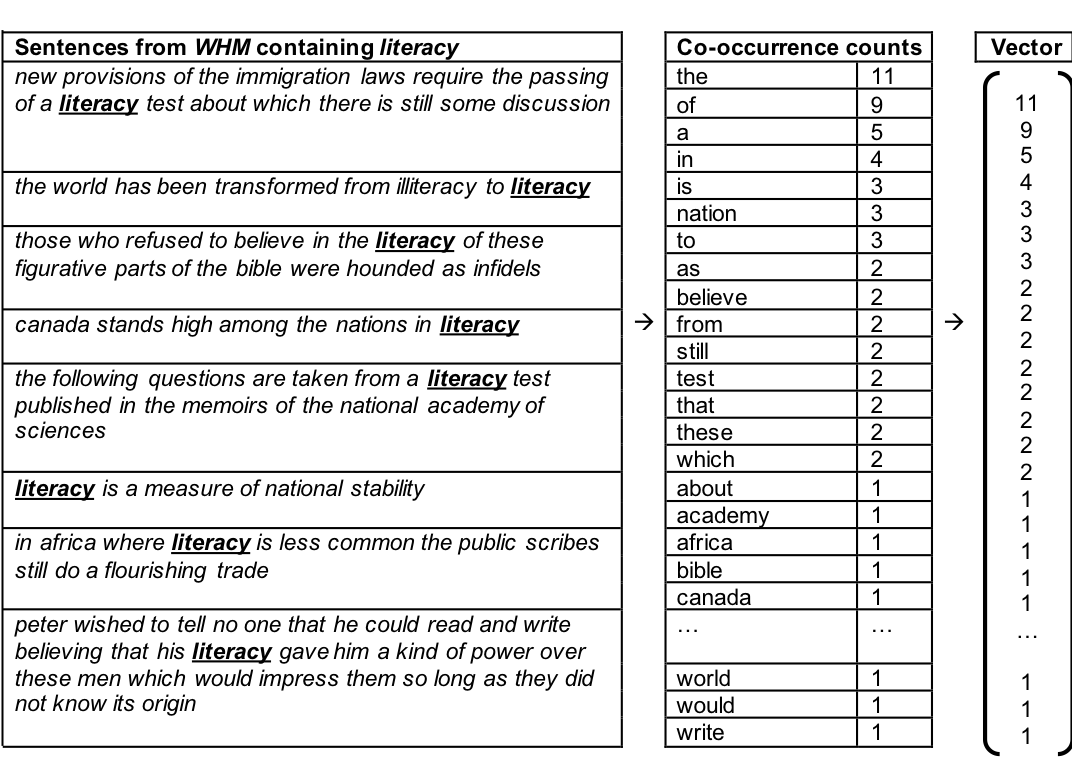

All this is more easily understood with actual examples rather than in the abstract, so here’s an example which uses a toy corpus of sentences from the Western Home Monthly (WHM):

This simplified example, which I have adapted from Erk’s useful article, shows how the vector of the term literacy would be obtained from the toy corpus. The sample sentences from the WHM are at the left, and from these are derived the context word counts in the middle, with the corresponding vector shown at the right. The toy corpus has been tokenized (ie. different forms of a root word have been reduced to the same root word), and word matching has been carried out between root words, so that, for example, national matches nations and believes matches believing.

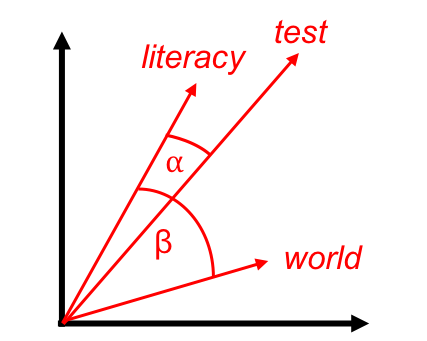

This list of numbers at the right - ie. the vector of the word literacy - can then be used as co-ordinates to represent literacy as a point in multidimensional space. Just as a point with the co-ordinates (2, 6) needs two dimensions to be plotted, and a point with the co-ordinates (2, 6, 4) needs three dimensions, so a point in multidimensional space requires as many dimensions as there are numbers in the vector. (Grasping how entities are related in high-dimensional space via intuition might seem beyond the grasp of most humanities scholars, but it is a simple enough matter for something like R to assemble in your computer’s memory.) And, the crucial final step: once a word’s location in multi-dimensional space has been plotted, its vector can be represented as a line on a graph moving from the origin—where the axes of the graph cross—to the point designated by the co-ordinates, as shown below:

Here, the similarity between literacy and test – calculated algebraically as the cosine of angle ⍺ – is closer than the cosine of angle β between literacy and world. For ease of visualization, multi-dimensional space has been reduced to two dimensions. Figure is adapted from Erk.

When all the words in a corpus have been transformed into vectors, the word embedding model is complete: the relationship of each word in the corpus to other words can be specified as a spatial relationship, and can thus be explored using linear algebra. One basic operation is to calculate the similarity between two vectors by taking the cosine of the angle between them, a measure known as cosine similarity. The image above shows in simplified terms how this is done. If two terms, literacy and test, have a small cosine similarity (ie. cos ⍺), they will tend to appear in the corpus in contexts that are more similar than the two terms literacy and world, which have a larger cosine similarity (ie. cos β). Following the distributional hypothesis, literacy and test are therefore more likely to be similar in meaning to each other than literacy and world. An important advantage of this approach means that words that appear less frequently in the corpus can still be reliably situated in vector space, as two words will be considered as similar if they have context words in similar proportions, regardless of their overall frequency in the corpus.

Of course, the question of what exactly is meant by ‘similarity’ is far from a settled one, either within literary criticism or the fields of computational linguistics and natural language processing (Stephen Clark gives an NLP perspective on this here). Similarity can denote synonymy, but may also for instance indicate words which can fill the same slot (eg. the cluster of personal pronouns – i me my you your – seen in the t-SNE plot above), or, as we saw earlier, even denote genre similarity (eg. errors). But it is here, in probing the ambiguities of what ‘similarity’ might mean for literary and historical discourses as they are, so to speak, embedded within the documents in a particular corpus, that humanities scholars have the most to bring to the word embeddings table. Some promising work here has emerged in recent years: Michael Gavin uses word embeddings to explore the ‘semantic space’ around the concept of rights in the work of Locke and texts in EEBO, while Lee et al. combine insights from word vectors, topic modelling and network analysis to build a persuasive case about how discourses around race in early modern English texts may be less to do with the body and more to do with geographical and climate-related understandings of space and difference. Another compelling example comes from Ryan Heuser’s work on eighteenth-century discourse, where he explores the analogical relationships between ideas such as virtue and riches, and genius and learning, showing how these can be captured via the process of vector subtraction. Paraphrasing Edward Young’s statement in Conjectures on Original Composition: In a Letter to the Author of Sir Charles Grandison (1759) that “just as Virtue does not need Riches but that Riches are wanted when there is no Virtue, so Genius does not need Learning but Learning is wanted when there is no Genius”, Heuser shows how one can

start with the semantic profile of “Virtue” expressed in V(Virtue); then, subtract from it the semantic profile of “Riches” expressed in V(Riches). The result is that the semantic aspects that they shared are removed, and only the aspects on which they differed left behind. This specific semantic contrast is captured in a new composite vector: V(Virtue-Riches). In natural language, V(Virtue-Riches) means Virtue as given by its distinctness from Riches. This new vector is not a word vector, but rather a particular relationship between word vectors—namely, a relationship of conceptual contrast, modeled as the relationship of mathematical subtraction.

This model thus holds out the tantalizing possibility of accessing a historically-situated network of conceptual and rhetorical relations, as well as exploring conceptual constructs that do not necessarily have ready-made descriptive labels. (I am not an eighteenth-century scholar myself but when I first heard Heuser speak about his work, what immediately came to mind was how useful word embeddings would have been to Samuel Johnson in writing his dictionary.) Heuser also stresses the importance of doing this computational work with a book-historical sensitivity to the different print culture forms (such as religious and political tracts) through which so much 18th-century intellectual debate proceeded, as these forms and genres would have significantly inflected the way that rhetorical relationships such as contrast and analogy—which prove so amenable to being modelled in vector space—were articulated. I have sought to capture a similar conjunction in my own work on the Western Home Monthly: a historically informed picture of the discursive and rhetorical connections between spatiality and nationality in this periodical that may be hard to pin down when looking at individual utterances, but which becomes more easily recuperable when modelled in vector space.

Notes: Ben Schmidt’s wordVectors package and the excellent blog posts that accompanies it (Vector Space Models and Rejecting the Gender Binary: A Vector-Space Operation) have been crucial to my understanding of word embeddings. These blog posts are a good starting point for anyone wishing to get started with word embedding models themselves (and Jon Goodwin has used Schmidt’s package to do some exploratory work on a corpus of Modernism/Modernity articles here). For machine learning more generally, the podcasts Talking Machines and TWIML Talk provide some useful background, and while they are not the central focus, word embeddings get an occasional mention. Ted Underwood’s Distant Horizons: Digital Evidence and Literary Change discusses machine learning methods alongside other algorithmic approaches in an appendix on Methods.

Added August 2020: Michael Gavin, Collin Jennings, Lauren Kersey and Brad Pasanek’s chapter ‘Spaces of Meaning: Conceptual History, Vector Semantics, and Close Reading’ in Debates in the Digital Humanities 2019 is a clear and compelling description of vector semantics and its utility as a method for approaching conceptual history.

The material on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please also drop me a line (see About) to let me know what you’ve done with it. Thanks!

The material on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please also drop me a line (see About) to let me know what you’ve done with it. Thanks!